Plant Construction Reaches Major Milestone

Ethanol plant construction was already running full tilt before the Energy Act was passed in 2005 and by the end of May 2006 it hit the major milestone of 100 facilities.

Ethanol plant construction was already running full tilt before the Energy Act was passed in 2005 and by the end of May 2006 it hit the major milestone of 100 facilities.

Approximately 1,200 people attended the grand opening celebration May 26 for the new $80 million Frontier Ethanol – the 100th ethanol plant to begin operations in the United States. The plant, which was built to produce 60 million gallons of ethanol annually from 21 million bushels of corn, was the 23rd ethanol plant built by Broin Companies, soon to be known as POET.

Ethanol was one of the hottest commodities in investment circles and on May 30, ethanol opened trading on the NASDAQ stock exchange with RFA President and CEO Bob Dinneen representing the industry during the opening bell ceremony. “Ethanol’s growing importance is being felt on Main Streets and more increasingly on Wall Street, and that is a good thing,” said RFA’s Dinneen. “While farmers have been and will continue to be the foundation of this industry, teachers, truck drivers, police officers and all Americans should have the opportunity to invest in our nation’s energy future.”

Absolute Energy broke ground in August 2006 in St. Ansgar, Iowa – Rick Schwarck, President; Steve Neely; Greg Goplerup; Chris Schwarck, VP; and Tom Edgington

Iowa had a big lead in terms of production with over 1.5 billion gallons a year in that state alone, with Illinois ranking second at half that amount. But states from California to Florida were boarding the ethanol band wagon.

It was hard to even keep track of all the ethanol plant announcements in 2006. Here is a post on DomesticFuel.com from August 8.

So Many Plants, So Little Time. Here’s a brief run-down of some recent plant related announcements:

Indiana – Premiere Ethanol and the Broin Companies broke ground August 3 on a state-of-the-art 60 million gallon per year ethanol biorefinery near Portland, Indiana. When fully complete, Premiere Ethanol will use 21 million bushels of corn and produce 356,000 tons of Dakota Gold Enhanced Nutrition Distillers Products™.

New York – Governor George E. Pataki has announced that Empire Biofuels LLC, an ethanol refining company, plans to invest $87 million to build a 50 million gallon per year corn-to-ethanol refinery at the old Seneca Army Depot in Romulus, New York.

California – US Farms Inc. has established a wholly owned subsidiary, Imperial Ethanol, dedicated to establishing an ethanol processing facility located in Imperial County, Calif.

Michigan – NextGen Energy, LLC, based in Southfield, announced plans for two ethanol plants to be built in Michigan. One will be in Watervliet in Berrien County in the southwest corner of the state. The other is in McBain, located in Missaukee County in the central part of Northern Lower Michigan.

Farmer Cooperatives Invest in Rural America’s Future

Ethanol plants became the hot commodity for investors in 2006, but farmers had already been making that investment in many rural communities.

Almost half of the ethanol plants in production in 2006 were owned and operated by farmer cooperatives or LLCs and accounted for 38% of total ethanol production. More importantly, they were contributing to the local economies despite being relatively small producers.

However, the influx of non-farmer capital into the ethanol market was already well underway, and there were fewer farmer-owned plants under construction, compared to corporate or risk capital-based ventures. According to the Renewable Fuels Association, only two of the 43 ethanol plants under construction in 2006 were majority farmer owned. By contrast, just three years earlier in 2003, almost 80 percent of all new ethanol plants that year were owned by farmers.

In an effort to discourage farmers from selling out their investment just as the industry was getting into high gear, the National Corn Growers Association (NCGA) released a study showing that local ethanol plant ownership generates significantly as much as 56% more economic impact than an absentee-owned corporate plant.

NCGA was quick to add, however, that they were not opposed in any way to the continued development of absentee-owned ethanol plants, they just encouraged ethanol project’s developers to “allow local investors to participate.”

While many cooperatives did sell out for a profit at the time, one that did not was Mid-Missouri Energy, a 40 million gallon per year farmer-owned ethanol plant that opened in 2005. In the fall of 2006, Wall Street investors turned up in the small town of Malta Bend, offering up to $275 million to buy the plant, which was started with just $22 million in equity. The New York Times interviewed the president of the plant when they turned down the offer.

While many cooperatives did sell out for a profit at the time, one that did not was Mid-Missouri Energy, a 40 million gallon per year farmer-owned ethanol plant that opened in 2005. In the fall of 2006, Wall Street investors turned up in the small town of Malta Bend, offering up to $275 million to buy the plant, which was started with just $22 million in equity. The New York Times interviewed the president of the plant when they turned down the offer.

“He didn’t really know what ethanol was,” said Ryland Utlaut, a veteran of 40 years of corn farming who is the president of Mid-Missouri’s board. “That bothers me. We built this plant.”

Mid-Missouri Energy is still proudly farmer-owned, but the shift toward corporate ownership of plants became the norm for the industry.

The 100 percent ethanol-powered Vanguard Squadron flying overhead for the grand opening of Missouri Ethanol in Laddonia, Missouri, September 2006. Missouri Ethanol was the nation’s 105th ethanol biorefinery and the fourth plant for the Show Me State.

The 100 percent ethanol-powered Vanguard Squadron flying overhead for the grand opening of Missouri Ethanol in Laddonia, Missouri, September 2006. Missouri Ethanol was the nation’s 105th ethanol biorefinery and the fourth plant for the Show Me State.

Missouri Ethanol was also the 25th ethanol plant built by the Broin Companies, soon to change its name to POET, which fell somewhere in between corporate and cooperative and had been steadily building biorefineries since 2003.

In June 2006, Broin announced it would hit one billion gallons in annual production volume that year, combining plants in operation with those under construction. That was equivalent to a quarter of the total U.S. production at the time.

By the end of the year, the company had 31 plants in various stages of development in Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota, Missouri, Indiana, and Michigan. In addition, Broin had entered the cellulosic race along with DuPont in a bid to make ethanol from corn stover biomass.

Cellulosic Race is On

One big attraction for ethanol investment in 2006 was grant money from the U.S. Department of Energy for cellulosic ethanol production, the search for the magical switchgrass that would take ethanol from corn to that next generation biofuel. But there were some companies that had a head start in the cellulosic race.

Canadian-based SunOpta started in the 1970’s designing and optimizing biomass conversion plants to develop various products. End products included cellulosic ethanol, cellulosic butanol, xylitol and dietary fiber for human consumption. Raw materials include wheat straw, corn stover, grasses, oat hulls, wood chips and sugarcane bagasse. SunOpta had a proprietary pretreatment system based on patented technologies they claimed as the “only industrially proven continuous system in the world for Biomass Pretreatment.”

In 2006, SunOpta had a number of cellulosic ethanol projects in the works around the world using its patented technology and equipment, including China Resources Alcohol Corporation (CRAC) in the People’s Republic of China; GreenField Ethanol Inc., Canada’s largest producer of ethanol; and Abengoa Bioenergy in Salamanca, Spain, the largest ethanol producer in Europe and the second largest in the world. Abengoa was working on a DOE-funded pilot plant utilizing the SunOpta system to be built at the Abengoa corn starch to ethanol plant located in York, Nebraska. In addition, SunOpta partnered with Celunol on a facility being built in Jennings, Louisiana, to produce ethanol from sugarcane bagasse and wood.

Another company with an early lead was Xethanol, a New York-based, Delaware corporation that formed in 2000 and got into ethanol production with two small plants in Iowa. In 2006, Xethanol was virtually the only public company working on making ethanol from cellulose and it benefited greatly from President Bush’s “switchgrass speech” in January 2006, causing its stock price to skyrocket.

Xethanol focused on genetically engineering proprietary yeast strains for the efficient production of xylitol from xylose, which could then be converted to xylitol. In 2006, the company announced plans to build new ethanol plants in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. However, Xethanol quickly ran afoul of the Securities and Exchange Commission and in September 2006, Xethanol acknowledged that it was not as close to the breakthrough technology as previously represented.

Canadian-based Iogen lays claim to having produced the world’s first cellulose ethanol fuel in 2004, from wheat straw and other lignocellulosics. The company had a demonstration plant running in Ottawa and in May raised $30 million in Canadian dollars (about $27.1 million) from Goldman Sachs to build the first commercial plant. Iogen was also hoping to be the first in the U.S. as it is working on a deal to build a plant in Idaho.

The demonstration plant operated until 2012, with a production capacity of 1600 tons/year, and is now being used for testing and validation of new processes and technologies.

In October 2006, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and DOE co-hosted a two-day national renewable energy conference in St. Louis, “Advancing Renewable Energy: An American Rural Renaissance”, to help create partnerships and strategies necessary to accelerate commercialization of renewable energy industries and distribution systems. Secretary of Energy Samuel Bodman and Secretary of Agriculture Mike Johanns opened the conference by announcing nearly $17.5 million for 17 biomass research, development, and demonstration projects. The conference was attended by more than 1,500 industry, academic, and government leaders.

In October 2006, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and DOE co-hosted a two-day national renewable energy conference in St. Louis, “Advancing Renewable Energy: An American Rural Renaissance”, to help create partnerships and strategies necessary to accelerate commercialization of renewable energy industries and distribution systems. Secretary of Energy Samuel Bodman and Secretary of Agriculture Mike Johanns opened the conference by announcing nearly $17.5 million for 17 biomass research, development, and demonstration projects. The conference was attended by more than 1,500 industry, academic, and government leaders.

The main day for the conference featured some 34 speakers and panelists, followed by ten more the next day, wrapping up with President Bush as the grand finale and the announcement that DOE would be using $250 million to set up two bioenergy centers for the development of new bioenergy feedstocks and processes for the next generation of ethanol plants fueled by biomass.

“And in my judgment, the thing that’s preventing ethanol from becoming more widespread across the country is the lack of other types of feedstocks that are required to make ethanol — sugar works, corn works, and it seems like it makes sense to spend money, your money, on researching cellulosic ethanol, so that we could use wood chips, or switch grass, or other natural materials.”

E85 in the Fast Lane

At the same time the number of ethanol plants was increasing, the availability of higher ethanol blends was growing as well. The production of Flexible Fuel Vehicles (FFVs) and availability of E85 had been growing slowly in the early 2000’s but that got a big shot in the arm with the Energy Policy Act of 2005 which authorized a number of government incentives focused on increasing the use and availability both.

It was the proverbial chicken and egg situation with the need to have the vehicles that could use up to 85 percent ethanol blended fuel and the retail stations to supply the fuel in the same place at the same time.

There were already millions of FFVs on the road in 2006, but the problem was the people driving them did not know what that meant or where to get this alternative fuel. There were only 762 E85 pumps in the entire country at the start of 2006, and many of those were private fleet pumps. With the support of the Bush Administration, that number would almost double by the end of the year.

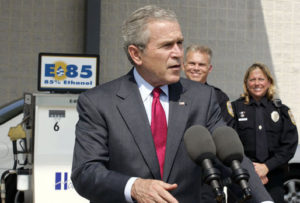

President Bush was pumping up E85 whenever he had the opportunity, including the Renewable Energy Conference in St. Louis.

Today there are 900 stations selling E85. For those of you who don’t know what that means, that’s 85 percent ethanol. Look, a lot of Americans wonder whether or not this is feasible, what I’m talking about. A lot of folks aren’t exposed to ethanol yet. In the Midwest you are, you’ve got a lot of corn. And it makes a lot of sense to have these plants where the feedstocks are. But ethanol is coming, and it doesn’t require much money to convert a regular gasoline-driven car to a flex-fuel automobile. See, the technology is available. It takes about $100-something to change a gasoline-only automobile to one that can use E85. And it works.

There were indeed E85 conversion kits that could be purchased and installed, and some took advantage of that option, but most of the growth in FFVs on the road came from the car makers who were incentivized to sell them, and the government fleet owners who were being required to switch to alternative fueled vehicles under the Energy Act.

President Bush talked about seeing E85 being used by the Hoover Police Department in Alabama. “Their people on the beat are filling up their cars with E85. I asked a guy, one of the policemen — I said, “Why do you use it?” He said, “First of all, I like the fact that it keeps the environment clean” — that’s a good reason. He said, “By the way, when you fill it up with the 85 it gives you better get-up-and-go.” In other words, it works. That’s a good sign when police departments begin to use E85.”The president strongly believed that ethanol was the leading edge of change in transportation energy as he told the audience in St. Louis. “It’s coming, and the government can help. That’s why we enhanced and extended the 10-cent-per-gallon tax credit. We did that to stimulate production. We’ve extended a 51-cent-per-gallon tax credit for ethanol blenders. We provided a 30-percent tax credit for the installation of alternative fuel stations, up to $30,000 a year.”

The government was also providing more funding to promote E85 and FFVs to local governments, businesses, and the general public. The National Ethanol Vehicle Coalition (NEVC) and the Alternative Fuel Vehicle Institute (AFVi) had been active since the ‘90s working on both the consumer level and in the fleet industry.

NEVC worked with General Motors on a public-facing FFV/E85 campaign in 2006 focused on helping consumers connect flex fuel vehicles with environmental friendliness. “Live Green, Go Yellow” was “an innovative partnership designed to promote E85 use and showcase GM’s E85 FlexFuel vehicle leadership to U.S. consumers throughout the year.”

NEVC worked with General Motors on a public-facing FFV/E85 campaign in 2006 focused on helping consumers connect flex fuel vehicles with environmental friendliness. “Live Green, Go Yellow” was “an innovative partnership designed to promote E85 use and showcase GM’s E85 FlexFuel vehicle leadership to U.S. consumers throughout the year.”

The yellow was meant to represent corn and the campaign promoted the now familiar yellow fuel-filler caps on its E85-capable vehicles to raise consumer awareness.

The number of public and private E85 fueling stations hit 1,000 before the end of the year, representing about 0.6% of the approximately 170,000 total stations in the nation at the time. Minnesota was the E85 leader in the US, with more than 300 outlets in the state.

From a very humble beginning of a few stations in Minnesota, Illinois, and Iowa, achieving this level of stations is significant,” said NEVC Executive Director Phil Lampert at the time. “In 1995, the year before NEVC was founded, there were 10 E85 pumps and 500 FFVs in the United States.”

In 2006, NEVC estimated there were six million E85-capable vehicles on U.S. roads, as compared to approximately 230 million gasoline- and diesel-fueled vehicles. However, they estimated that less than five percent of those FFVs were actually being fueled by E85 because it was either not available or the car owners were unaware of the capability.

The majority of stations were located in the five highest ethanol-producing states: Minnesota, Illinois, Iowa, South Dakota, and Nebraska. At the same time, the majority of the FFVs were located in states like California, Florida and Texas.

In November, General Motors, Ford and DaimlerChrysler met with President Bush and pledged to make half of new vehicles manufactured FFVs by the end of the decade, a move considered to be another major win for the industry in 2006.